By Andrew Farrell

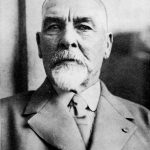

Captain John Cameron Midway Island, February – 1888

Midway Island, February – 1888

John Cameron’s Odyssey

AT MIDWAY THE “MINSTREL” ENDS HER WANDERINGS,

AND MINE LIKEWISE PAUSE UNEXPECTEDLY

On the day after Jorgensen told his story Walker and I made a surveying cruise in the steam launch to Eastern Island and about the lagoon. Thus familiarized with Midway and its reefs, we began to land gear for shark fishing, Hanker being in charge of one boat and Jorgensen of another. We took ashore a great quantity of thin boards and scantlings, which we intended to use in building sheds; two fifty-gallon pots for trying our sharks’ livers; a few hundred knocked-down barrels for oil; a blacksmith’s forge and grindstone; and innumerable other articles necessary and unnecessary. All hands pitched to this preparatory work, eager to get to grips with the sharks; and while we were working, Walker and his family went picnicking in the launch.

After such an excursion Walker rushed on board in high excitement. “Our fortunes are made, Mr. Cameron!” he exclaimed. “Get rakes, with nets attached, ready at once. The whole bottom of the lagoon is swarming with beach la mar!” Now at that time beach la mar was worth about seventy-five cents a pound in the markets of China, where it was, and still is, highly esteemed as an ingredient of a delicious soup. But I knew that scarcely any beach la mar was to be found at Midway; nevertheless had equipment prepared, with which Walker began his hunt. After a hall day he and his fishermen returned with a large quantity of ordinary sea slugs, worth possibly ten cent a hundredweight as fertilizer. In order to convince him of his mistake I asked, and with difficulty won, permission to make an expedition of my own. For a whole day, I made a thorough search of the entire lagoon; my spoil was a half dozen specimens of true beach la mar. Yes, Walker at length admitted, he had been wrong.

In general everything was running smoothly; the men were contented, they had plenty of eggs, fish, and turtle flesh in addition to usual ship’s rations; they obeyed orders willingly; and all of us were anxious to begin our fishing. A dwindling store of water did not inconvenience us, for by sinking headless barrels in the sand we got an inexhaustible supply. Indeed, fresh water could be found in the sand beach only ten feet from the salt tide.

But all could not possibly go well for long. One morning, in the altercation with Walker, Hanker used vigorous language and added a few pointed and truthful accusations. Goaded to fury, Walker shouted, “Bring the handcuffs, Mr. Cameron, and put this man in irons!” “Here you are, Captain Walker,” said I, handing him the irons but never dreaming that he would carry out his threat or that Hanker would submit to such degradation. To my stark amazement, however, the second mate meekly extended his hands; nor did he make the slightest protest as the captain snapped the handcuffs to his wrists. “Take him forward,” Walker ordered me. “He’s no longer second officer. Confine him in the forepeak; secure the door. I’ll teach him who is master.” Without a word Hanker walked forward and descended into the forepeak, where he seated himself to brood over his misfortunes. “I’ll be damned if I’ll lock the door,” said I to him. “Give me your word that you’ll not go on deck to raise hell with Walker.”

When Hanker had pledged himself to make no trouble I went aft to remonstrate with the skipper and to urge that he release the mate. The only reply I could get was that irons and imprisonment were necessary for discipline. “Why not note the trouble in the log?” I demanded. “Why not send Hanker to his room as punishment for insubordination? He did not use threatening language; he is not a dangerous person. He’ll never be able to control the crew again.” “He’s no longer an officer,” retorted Walker. “I’ll appoint Jorgensen in his place.”

Taken aback though I was by such summary disrating, I continued to argue with Walker and at length won his engagement to free Hanker if the mate would apologize; but this Hanker steadfastly refused to do. “He’ll wish himself in hell before I’m through with him!” cried the skipper. Having expressed himself thus kindly, Walker rushed below, to return with a fathom of quarter-inch chain, which he ordered me to put about the prisoner’s ankles and secure to a stanchion. “I deliberately refuse,” said I. “There go your chain lashings overboard. Do your own dirty work.” Surprised into speechlessness, the skipper went below and did not reappear that day. Next morning he greeted me cordially,—neither of us alluded to Hanker.

Jorgensen proved himself a hard worker and an efficient second mate. With his assistance the work of landing gear proceeded expeditiously. During most of January and the first part of February we were busy preparing for our great sharking venture. Except for occasional rain and wind the weather continued good; but Jorgensen warned us that it would be dangerous to remain in Welles Harbor too long; and I decided to ascertain whether we could get the vessel into the lagoon, where we might moor in safety. Between us and a satisfactory anchorage were many rocks above and below water; still I believed that I could find a passage. A survey disclosed sufficient water for the MINSTREL Little danger was to be apprehended in calm weather and a smooth sea, provided only that the craft was handled properly. Apparently impressed, even elated, when I reported my findings, Walker decided to move into the lagoon at the first opportunity.

Favored by good weather, we landed all gear safely; then began to build sheds and assemble our knocked-down barrels. Yet I did not neglect to impress upon Walker the urgency of changing our berth. Finally, after much persuasion, I won his grudging consent. Early one morning, when the weather was quite good, we raised steam in the launch, hove the anchors, and with me in the launch as pilot, began to tow the MINSTREL into the lagoon. Everything was propitious; not a breath of wind blew; not a ripple flecked the water. We were making good headway, to my gratification, when Walker dropped anchor in five fathoms of water, and not content with that, permitted too much chain to run out and thus left a foul moor. “It’s too risky,” he said when I asked why he had anchored. “I’ve decided to remain in Welles Harbor.” Knowing that argument was useless, I contented myself with warning him of probable disaster. We then swung the vessel’s head and dropped the second anchor after which I called Walker’s attention to the length of chain that had run out with the first. “Nonsense!” he exclaimed. “The anchor isn’t foul.”

Within two days stormy weather opened. In a heavy swell chains and windlass were subjected to hard strains. Each night I examined the windlass to make sure that all was well, and I gave the boatswains strict instructions to see that the riding pawls were in place, for I had scarcely forgotten that Walker had un-shipped them at French Frigate Shoals. One midnight there occurred what I had dreaded and half expected: a boatswain called me to report that the windlass had been smashed. It was indeed out of commission for the remainder of the voyage. Although everything had been in order when I went below, the riding pawls were not in place: the captain, the boatswain explained, had un-shipped them and had ordered that they be left alone. As a consequence of this criminal folly the anchor chains were run out to the bitter ends, but since they were well secured and nothing could be done in the dark with our apology for a crew, I went below to wait sleeplessly for dawn.

After coffee had been served I roused the men out; got two coils of four-inch Manila rope, each of four hundred fathoms, specially made for the WANDERING MINSTREL in Hong Kong; and with three- and fourfold purchase blocks reeved tackle to extend from the waist of the ship on each side to the anchor chains. This would enable us to heave in superfluous chain and would ease the strain on the broken windlass: and the considerable give and take in the rope enabled the vessel to ride comfortably enough. In no wise put out by the mishap, Walker commended me for rigging such an effective riding substitute. Yet I felt sure that he realized I had penetrated his scheme, which was nothing less than to lose the vessel in such a manner that he could not be brought to book. He did not wish to return to Hong Kong; of that I am convinced. Already the expedition was a failure: six months had passed of the nine he allowed himself; only three months remained in which to make good his promises of fabulous wealth. No wonder he would have welcomed a fortunate accident. Not at all; Walker was left in no doubt as to what I thought. That came within a few days, when more moderate weather permitted us to shorten our mooring chains. While this was being done my fingers were jammed in the gear because Walker gave the men an unexpected order to pull. After making the air blue I quit work for the day. In the evening the skipper sent a box of cigars as a peace offering: a surprising gift, for in the morning I had accused him pointblank of attempting to wreck the ship. During the next few days we had better weather, but that did not deter Jorgensen, a born pessimist, from predicting disaster; and I was inclined to concur. If trouble arose we should need every man. That consideration,taken with Hanker’s increasing despondency, led me to beg the skipper to release the second mate. Walker, however, still demanded an apology, while Hanker was determined to make none. Soon he developed a high fever and became delirious. Walker refused to give me the keys to the handcuffs; he did surrender when I threatened to cut the irons from Hanker’s wrists. I freed the poor devil; gave him a dose of ship’s medicine which Walker at last let me have after pleading that he did not know what to prescribe; and all in all I made Hanker as comfortable as I could. Then I set a man to watch him, lest he harm himself or the vessel. Within a few days, when he was well enough to be up, I assumed the responsibility of allowing him to go to the wardroom.

Again we had stormy weather, and this time I anticipated a prolonged siege, the month being February, a season of high winds in the latitude of Midway. Increasing wind and sea compelled us to give the MINSTREL more chain in order to forestall her dragging her anchors, inasmuch as a flat and rocky bottom, covered with a heavy silt of sand, was hardly good holding ground. A gradually falling barometer and the actions of the sea birds, which hung about the island and would not put to sea, foreboded weather still more nasty. For it we took every possible precaution; battened down the hatches; secured the steam launch to the davits; braced the yards up sharp; overhauled the riding tackle. Notwithstanding these precautions I had a presentiment that, unless a miracle intervened, the MINSTREL would come to grief. Our anchorage was far too exposed to gales from the northwest, which prevailed in the winter months, and was open to the sweep of the sea through the channel when the wind blew from quarter.

Not merely a high gale but a storm of typhoon force was forecast by the barometer. Soon the wind was strong enough to alarm us, for less than two hundred feet distant a reef was breaking with heavy surf. It was a most disquieting outlook; should the vessel drag her anchors at night she would pound to pieces in no time, and all hands certainly would perish. Even now she was rolling hard, broadside to the seas, since a strong undertow, running from the reef, swung her stem well up into the wind. To her sore labor the weight of the launch contributed materially. If the boat was lowered into the sea water and allowed to drift over the reef into a smooth sea, where we could anchor it with a tripping rope, the ship would be immensely relieved, I said to Walker. His assent given, we put the idea into successful execution. Relieved of the weight, the MINSTREL resumed an even keep and did not roll so hard. But this was merely a palliative and no remedy. Our situation, as a blind man could see, remained most grave. With all available anchor chain paid out and a jagged reef dangerously close, we gazed fascinated into the jaws of destruction.

Now the room was blowing with hurricane weight, accompanied by squalls of increasing violence which I do not know how to describe, seeing that “hurricane” and “typhoon” are the strongest words knows to a seaman. The roar of the surf, coupled with the shrieking of the wind through the rigging, shattered our nerves. What would happen at night we could only conjecture. Nothing remained for us to do but pray that the anchors and chains would hold. Yet we apprehended the worst, such was the fury of the blasts and such the tremendous force of the gigantic waves rolling in from the deep sea.

Then the skipper, finally realizing that we were in precarious straits, showed the white feather. “What shall we do?” he asked. I replied, “The vessel’s stern is well up to the wind. Set the lower topsails, slip the anchors, run inside the lee of the boulders, where the water is smooth, and drop the spare anchor. It will require less than a half hour. After that the ship will ride in safety. But my suggestion appalled him. Was it too daring? We were in a perilous state. With a ragged reef, foaming white with heavy breakers, on our lee, we had to attempt something to ward off a closer and deadlier acquaintance with those rocks. After much consideration, however, Walker dismissed my plan as impossible to success with our crew. “Too desperate, Mr. Cameron.” he added. “I am afraid the bark would sag upon the reef before gaining headway.” In answer I demanded, “How can that be? The wind is in her favor; as soon as the topsails are sheeted home she will forge ahead. The chains are all ready to unshackle. Come, make the attempt. Let me set one topsail before slipping the chains. I’ll stake my life on the outcome.” Still he demurred: “We would drift down upon the reef and meet with the very ruin we are trying to avoid.” Further discussion was useless, for he was determined not to try what I firmly believed could be accomplished, aye, and was ready to risk all our souls, my own included, on the result. But Walker was not the first man who awaited a miracle; and I was the last to hope that God would save those who made no effort to help themselves. Surely the Deity and Storms expects man to play a man’s part.

Walker rejected my expedients; yet he himself, press him as I would, had nothing to offer. “Then for God’s sake,” I cried, “run to the sand beach. The ship will not be damaged much and can be refloated when the gale has passed. To leeward of the boulders there is little swell, not sufficient to harm her. Slip the cables, and run!” No man of decision and courage would have hesitated. But Walker still protested. He refused to attempt everything that promised salvation: he and he alone was to blame for the ensuing catastrophe.

No signs of the tempest’s abating were apparent: the barometer continued to fall; the MINSTREL labored ever worse in the huge seas that hurled themselves into the harbor; outside, as far as we could see, the ocean was a seething, heaving mass of white-crested waves that broke furiously on a long expanse of shoals. Again at dinner I urged Walker to adopt one or another of my plans. “You see that the weather is getting worse,” I argued. “Not yet has the full force of the storm struck us. When it does, mark me! the anchors can’t hold. The bar will be smashed to pieces in a short time. I would give her no more than two hours after she struck. God help us all if that happened at night. Not one would be saved.”

Again Walker returned an uncompromising negative. “One other course, and one only, remains,” said I with all the finality I could muster. “Cut away the masts. With them over the side the bark will ride out the storm.” “My God, Mr. Cameron!” exclaimed Walker. “That is a last resort with a vengeance. Some of the crew inevitably would be killed.” “Some had better die than all,” I countered. “We could secure the spars, Captain, and give the vessel a jury rig afterward. Grant me permission to cut away. I am confident that none of the men would be hurt. Dismasting is neither difficult nor dangerous. With it done, even though the vessel should drive upon the reef,–as I don’t believe she would,–the hull, relieved of the strain of the masts and yards, would hold together long enough for us to take to the boats.”

Receiving his unqualified rejection of this plan, because, he said, “we might weather the storm,” I went below for a smoke. Jorgensen’s renewed croaking of disaster rang in my ears as I began my watch on deck. Ominously the night opened. One squall on the heels of another tore through the rigging, while amid their wail arose the unbroken roar of the surf upon the reefs. What a night!–and a long one, for I had no sleep. It was as black as “the Earl of Hell”s riding boots,” except when prodigious flashes of lighting disclosed a scene wild enough to terrify the most courageous.

At daybreak on February 8, 1888, the wind was extremely severe. Spindrift, driving before it, stung our faces like hail. Still the barometer fell, until the sole question seemed to be how long our anchors would hold, not whether they would; but at dawn the lead line showed that the MINSTREL had not dragged from her position of the night. That and the day, though feeble and wan in a world of raging tempest, cheered me immensely. Different indeed is a man under the light of the sun from the same man at night, when terrors are hidden and magnified.

As the weak daybreak waxed, the wind blew with renewed fury; seemingly in accord the breakers mounted to overwhelm us: storm and sea gathered to annihilate the WANDERING MINSTREL. To my dismay the lead line now showed that our position was appreciably altered. Therefore I ordered the cook to hurry breakfast, and told the men that the meal would be our last on the vessel and that they should stow away plenty of food; but the poor dolts, instead of doing that, went to pack their kits,–which they were compelled to leave behind. How strange that a man should risk his life for a little trash when the world overflows with trash to be had for the taking! Greatly agitated, the captain appeared on deck; his courage, however, was raised when he handled the lead line and detected no movement of the ship. But a brief abatement in the high severity of the storm misled him; and I, completely disgusted, made no response to his optimistic report.

On the heels of that lull a rain squall of cyclonic fury brust upon us. Heavy black clouds, close overhead, twisted and hurtled down to leeward, turning the dim day into sullen dusk. “Now for it!” I ejaculated. “The MINSTREL can’t stand this!” Even as the thought ran through my mind the bark bumped and shivered from stem to stern, while her masts and yards whipped like cane in all directions. Wave after wave, roaring from the sea, drove us ever closer to the reef, and after each heave the MINSTREL pounded hard. She was doomed, yet we could do nothing to save her; we could hardly lift a finger to save ourselves until the hull, by fixing itself solidly on the rocks, should give us a lee for launching the boats. In such circumstances I could think of nothing better to do than stand in a sheltered place and watch my predictions of catastrophe being borne out to the letter.

Walker rushed forward with an infantile question” “What are we to do, Mr. Cameron? She’s struck! “Save lives!” said I; “save lives, you damned idiot!” “Oh,” he wailed. “how can we? No boat could live in that surf. Captain Walker, what other chance have we” I inquired. “Oh, he replied, “the weather might moderate before the vessel broke up. I prefer to remain on board rather than risk landing in a boat.” “Yes,” said I most softly, “and Elijah may carry you aloft in a feather bed. Listen to me, Captain Walker,” I barked, “the vessel will be in pieces before many hours have passed. Go immediately and assist your wife and children to get ready to leave the ship. They must go ashore in a few minutes. We now have a good opportunity, for the ship is well up on the reef with a smooth sea on the port side.”

Even then he hesitated; so I ordered him to start, then caught him by the shoulders and propelled him aft. Lying broadside to the reef, the ship did offer an excellent lee and gave us the best possible shelter for launching the boats. “Pack only useful articles,” I called after Walker’s retreating form. “We can’t overload the boat.” At the same time I instructed Jorgesen to place a bag of biscuit in the craft. This he did;–and the imbecile of a captain threw it out to make room for something of far less value.

When the boat was ready I ran to the cabin to prod the Walkers. Delay was becoming dangerous, what with seas sweeping the weather bulwarks and the wind casting spray above the top mastheads. On the steps to the cabin I met the skipper. “My wife insists that I accompany her and the children,” he informed me. “You can go to hell for all I care,” said I; “my cone concern is for your family.” I succeeded in getting them into the boat, and Walker followed; the men, however, refused to start without me. I agreed to go; but leapt back to the MINSTREL as the lines were cast off; and once under way the boat could not return. Even as it left the ship’s side Walker gave me some final instructions, senseless like the rest. In a few seconds the craft met the surf and then, thank God, his voice at last was drowned.

Our other boats, which offered the only salvation for those who remained aboard, were on the weather side, exposed to the storm. To get them to the shelter of the lee side was difficult; it entailed the hardest driving of the terrified crew. When the boats had been moved a more trying time began. Scared out of their wits, the men were unable to help themselves, even to carry out my orders except under threats, some of which had to put into execution. That I also was frightened I confess now, but I was too proud to let any one suspect the truth then.

As we were about to leave the ship it occurred to me that tobacco would be relished on shore, and ordered a Chinese boy, who I had christened Moses, to fetch a box from the storeroom. He returned without any: the storeroom, said he, was flooded. “Come, come, Moses,” I chided him; “make look-see.” Sure enough, the room was full of water, while boxes were washing about as the vessel reeled. Hazardous indeed it was to secure anything except tobacco, but I was determined to have. “Go ahead, Moses,” I encouraged him; “can do. I look out for you.” “No can,” he wailed in mortal terror; no go,” I retorted grimly. Then I threw him into the maelstrom. He emerged with a box of tobacco, on which, I suppose, he had happened to fix a grip of death. Fortunately he was not injured. I relieved him of the precious package; nor did I fail to praise for his involuntary courage. “You velly smart fellow, Moses.” That tobacco was all I myself took from the wreck, except for the clothing I wore, and it was in ribbons when I landed; but Jorgensen,, foreseeing that I would be occupied with the crew, packed with his own effects some of mine, including my sextant. Within a few months it was to be useful enough.

By this time the storm was howling fiercer; the seas were rolling on board in greater volume; the surf arose higher and blew, before harder blasts of wind, in a solid smother of foam between us and the beach. No man could have said where air left off and water began. At any moment it seemed that the masts must go, while the aged vessel’s hull groaned in torment even above the tempest. Hurry was the order of the day, but difficult to carry out, for the crew, seized with blue funk, sat on their boxes like so many sick monkeys.

Although he was not fully recovered, Hanker assisted in getting the boats alongside without one being smashed–a difficult proceeding; and he also volunteered to handle one of the craft. Off we started, my boat in the lead. My men were too frightened to use their oars, which I therefore ordered held aloft, since the boat could easily slew broadside and capsize if a single blade should strike. Hanker’s men followed our example. Driving before wind and sea, the two boats flew through the white smother at terrific speed. How high was the storm may be gathered from the fact that Walker’s craft, which had been drawn up on the sand, was bowled over, end for end, as we neared the beach. My men landed without mishap, thanks to my instructions that they should leap out lively and grab the boat when it met the sand,–this to prevent the undertow carrying it back. But the second boat was caught, and Frank Lord, the cook, was washed underneath it. He was extricated uninjured, although to free him required the efforts of all. Then we hauled both boats well up on the beach, beyond the reach of the sea; we carried back Walker’s craft, which had been blown about fifty yards; and lashed the three of them together for greater security. At last I could breathe freely. I shuddered as I gazed over the smoking sea through which we had passed; I thanked my stars that I had experience with surfing in Hawaii.

We had escaped, but with little besides our lives. There we were on a desert island, without provisions, aside from some ham and bacon. Shelter was available, however, as Jorgensen vacated his cottage for the Walkers, while he and I took up our quarters on one side of the veranda. The men built themselves shanties from the boards that had been landed for the construction of sheds, and heaped sand about the shacks to buttress them and keep out the cold. With fires burning, the huts were quite warm and cozy. Hanker, who continued to brood over his humiliation, who indeed seemed mildly insane, occupied a hogshead at some distance from the others. Though it resisted rain and wind, his barrel was more than cramped. From us all he remained aloof, venturing out only in the gloaming to capture some of the myriads of small crabs that infested the beach and then, like one of the animals, scuttling back to his queer house, there to make soup of his quarry. After the first two days, when a commissary had been organized, there was no need for him to forage: I saw to it that he received a portion of what was brought in. This was principally eggs and fish, and was about all we could expect from the island. How well the supply would last in view of our number, and whether we would thrive on such a diet, gave me great concern. Fortunate it was that Jorgensen had collected such a large number of gony eggs, about ten thousand, as I have said, and that more eggs, ranging in size from a lark’s to a goose’s or turkey’s, were obtainable from the nests of numerous species on Eastern Island.

Before nightfall on the day of the wreck I tramped along the beach to have a last look at the WANDERING MINSTREL and to ascertain whether the surf was subsiding. At the least indication of moderating weather I entended to muster a volunteer crew, board the wreck, and load a boat with provisions. The storm was still raging, however, while it was obvious that the bark would soon break assunder under hard hammering. How long would she hold out? As though in answer to my speculation the foremast and mainmast crashed over the side, dragging with them the mizzen topmast. Only the mizzenmast remained standing, a solitary sentinel, or rather a monument to a vessel dispatched to her doom.

Day was settling into night when I bade the old MINSTREL farewell. Many sailors look on their ships as almost human and regard a wreck with some such sadness as they would feel in gazing on the corpse of a dear friend. Why not? Does not a ship have her moods, her whims, her vagaries? Is she not vibrant with life, as if pulses ran through her frame? Must she not be watched with unremitting vigilance, like a beautiful and beloved but capricious woman? Does she not bear the hopes and fears of men from port to port, even as our lives center about women from the cradle to the grave?

Cold and hungry when I reached the cottage, I gladly sat down to a meal with Jorgensen. One could have a worse dinner than what he served: egg pancakes with tea of beaten eggs and hot water. To say that I slept that night would be hardly accurate; I suffered a temporary death, so fagged was I by the eventful day and the sleepless night preceding. I was resurrected when Jorgensen called me to breakfast. And such a meal: boiled eggs, each weighing nearly a pound; an omlet, egg bread, or pancake; again washed down with egg tea.

“How old is the ship, Jorgensen?” I inquired. “She has disappeared,” he reported; “not a trace left. Everything, so far as I can make out, has gone, likely enough swept to sea. No sign of the launch, either, though it would probably be pushed before the wreckage as it drove over the reef.” After breakfast I tramped about the island in search of something from the MINSTREL, and was rewarded by finding part of the stern washed inshore. On wading out to it I was delighted to discover nearly all the awnings and a few sails. Jammed with the canvas were the fragments of Walkers piano. Much to my surprise there was something else: a rule that in some inexplicable manner had got there from my cabin to the main deck. It was on of the few things I saved after twenty-one years at sea.

The canvas, I immediately saw, would be of immeasurable utility: we could unravel, knot, and spin it into twine for fishing nets; the wires of the piano might be used for making hooks. Indeed a piano did have some value. We salved the sails and awnings and drenched them with fresh water; otherwise the canvas, being saturated with salt, always would have become damp in wet weather. The steel piano wires we rubbed with oil to prevent rust. With hooks made of them we caught many fish, a variety of albacore, so large and strong that I have seen two men dragged by one from the beach into the sea, fighting hard and hanging on until the fish drowned and was hauled ashore after a struggle of a half our. How much the fellows weighed I had no means of determining, but I thought, since one of them, slung on a pole, made a load for two men, that they would average about a hundred pounds. They were excellent eating and meaty as well, the head along being sufficient for ten persons.

While I was playing the wrecker, Captain Walker met me with the tidings that the crew refused to obey his orders–“You saved some firearms.” “Would you shoot one of the men?” he demanded. “I shall muster the men in line,” said I; “the first who refuses to obey you will be shot.” “Good God!” he exclaimed. That would be murder.” “Not at all, Captain,” I assured him.” I’ll not shoot to kill’ merely to wing—-” “I’ll never consent,” he interposed. “Perhaps I can persuade them by gentler means.” “Do not delude yourself, sir,” I urged. “I know these cattle better than you do. “They must be kept in hand;” dealt with firmly, taught, especially now, too look up to us as their superiors and masters. What is it to be? Do you consent to my proposal?” “Mr. Cameron, I do not; that is final.” “Very well, Captain Walker, you must paddle your own canoe. Nothing remains to be said except that we are all equals now and that each is a law to himself. I shall, of course, protect your wife and children.” Eventually Walker was to realize his folly, as I shall explain in due course.

In thus declaring my belief that respect for authority, the foundation of our little society, had disintegrated, I was sincere: I fully expected the men to disobey me when I ordered them to work; but one and all eagerly carried out my instructions. Some of them I sent to salve the awnings and remaining sails and the piano, as well as to secure what was left of the wreck from drifting away; the others I took with me to Eastern Island, where I hoped to find part of the ship on the beach, for I reasoned that the wind should have driven some floating fragments thither. Search the island as we would, however, no wreckage did we find, except an iron kettle, the lid of which was missing, and a silver-plated fork, both well above high-water mark. Neither had come from the WANDERING MINSTREL: Jorgensen recognized them as from the GENERAL SEIGEL. The kettle was put into service to boil eggs for the cabin passengers; the men perforce continued to roast theirs.

Eggs! They were brought in by the hundreds, of different kinds and sizes. Rapidly did they melt away, so hungry were our men. Such myriads did we eat that I do not understand how I can stomach an egg to-day. Obviously the first and second officers could not lag behind the forecastle; Caucasian prestige had to be upheld; in one sitting Jorgensen and I disposed of thirty nine, hen’s size. Unhappily that is an uneven, an odd, number; hence it became a topic of hot debate whether he or I had devoured the last one and so earned the egg-eating championship of the Northwestern Pacific.

Notwithstanding their weight, relative and absolute, in our diet, eggs did not constitute our sole food. Here I may give one day’s menu: Breakfast–fish boiled or fried, egg pancake, egg tea. Dinner–beach la mar soup, minced flesh of sea fowl, fried fish, egg pancake. Supper–egg tea, cutlets of sea birds, egg pancake. And now that I have mentioned beach la mar soup, I am impelled–compelled–to give my own recipe for this delicious dish. What I have to say should interest the epicures of London, Paris, and New York, in whose restaurants it is seldom found. First, then, get your beach la mar. Where? There is a little at Midway. Parboil it; cut it open; smoke and dry; slice it into inch cubes. Boil a number of these pieces for three or four hours; add small sea birds, well cleaned,–they can be got at many a desolate oceanic rock; put in grated wild radish. Must I say where that also is to be had? When the whole has been well cooked, remove it from the fire and let it cool a little. Then beat thoroughly a few eggs of sea birds–tut! tut! here I am prescribing other unobtainable ingredients; pour this froth into the soup, replace the pot on the fire, which is best made with coal left by the Pacific Mail on Midway Island; barely let the mixture come to a boil. Finally, and this is most important, season with nothing less than the appetite I had on Midway. Easily done? Doubtless.

From danger of starvation, then, we were freed by eggs, sea fowl, and fish. We caught many of the last two nets which we made of the threads of unravelled awnings spun into twine with improvised hand jennies of bamboo; the first net, sixty feet long and four wide, having a mesh of two and one-half inches, kept us well suppled with fish, but it was neither long enough not deep enough to encircle a school of mullet; and we therefore made another seine one hundred and twenty feet long and six deep with a two-inch mesh. It enabled us to catch many mullet, frequently more than we could land, some of them twelve pounds in weight, digestible and delicious whether boiled or fried. Unlike most of the dry fish of warm seas, they had thick layers of fat on their bellies. Hordes of sharks, by chasing the mullet into shoal water, unwittingly assisted us; but those same devils gave us little opportunity to feast on turtle, for they devoured the young reptiles. Moreover, we snared curlew with twine and kept them in pens handy for the table.

Day after day we fanned the hope that a passing vessel would rescue us; days became weeks, and weeks months, and hope burned low. Why despair? We made the best of things. For me the crew worked willingly, though they would not move a hand for Walker. “Why?” I asked a boatswain. He replied that the men realized that the wrecking of the MINSTREL was the captain’s fault; he was to blame for their being cast away, for the loss of their effects and probably their wages as well. That they dwelt so insistently on their few belongings and scanty pay when all of us were dodging death may surprise some, but not those who know the peoples of the Orient and how little constitutes wealth for them,–those swarming millions who are born in poverty, live in hunger, and die in want. Since they would not obey Walker the men turned naturally to me for leadership, and they fell to work all the more gladly when I explained to them that idleness would affect their health and make them more subject to scurvy. Directing them kept me busy enough, but I did miss books. The only one on the island was “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” and that I must have perused once a week.

In this new atmosphere of cheerfulness Hanker along remained morose, still lived as a recluse in his hogshead. Try as I would to cheer him, I signally failed, because, I firmly believed, his mind was deranged. His bodily health, however, was restored, a fact that did not pass unnoticed by thee men, and they were most unwilling to share their food with him,–right enough, too, from their standpoint, since he was capable of foraging for himself.

Milder weather increased our good spirits. Men as scantily clad as we were welcome the northward swing of the sun; but soon we had to rig an awning to shelter us from its rays while we worked. Oncoming spring and summer did, however, help us to solve the serious problem of clothing. Now we could spare our few garments by going clad in loin cloths. What of yet another winter? Well, that bridge was still distant; if we had to cross it we might manufacture canvas uniforms. Making shoes was out of the question; our bare feet would wear much longer than leather, so unshod we went, though we suffered severely until the soles hardened and we could run over sharp coral without hurt.

For three months every one remained in the best of health. Then some of the men fell ill of a malady none could recognize. We had no medicine to help them; probably nothing would have availed. Their sickness was of the mind or soul; they lay inert and drowsy, and we whites could not rouse them; day by day they became weaker, though suffering no pain, and died so peacefully that their passing scarcely seemed death to one who had witnessed the violent struggles of white men against extinction.

In truth our monotonous diet of fish, flesh, and eggs was threatening to endanger the health of all. Then the fortunate discovery of a tierce of rice from the WANDERING MINSTREL cheered our hearts and stomachs. The cask probably had been submerged since the wreck and not had risen to the surface, I conjectured, because water had penetrated to the grain and created gas by fermentation. Impregnated with salt though it was, the rice came quite palatable after being soaked in fresh water. In its division we all shared alike, notwithstanding the skipper’s claim of double portions for their wife and sons, whom he described as passengers and so entitled to more. To this demand I replied that distinctions were erased when the vessel was lost. How quickly the others ate their small shares I do not know: Jorgensen and I husbanded ours and actually debated whether we should count the grains to be allotted to each meal. Never before, I think, had I grasped the value of food. We did not, indeed, waste the fresh water in which we had soaked the rice. Happening to notice that the liquor was fermenting, I boiled it down and obtained a good substitute for sowens, a Scotch dish made from the farina which remains in th husks of oats.

By exercising such care, always with something to occupy myself, I remained in the best of trim during my eight months on Midway. My sole lllness, of only six hours’ duration, was caused by my eating a mutton bird, a mass of fat that tempted me to gluttony. That sickness is not the only indictment I bring against the mutton birds: the first time I heard one crying I received a sharp shock of fright, so mournful, uncanny, unearthly were its wails as it sallied from its underground nest to search for food in the gloaming.

Day pursued day and month followed month in monotonous procession;-and still no rescue That was no reason for despair; but it was cause for us to help ourselves. With this in mind and also to provided work to keep us from moping, I suggested to Jorgensen that we construct a craft of some sort from the lighters upon which he had drawn for the veranda. If we did build a vessel, however, I designed it only for Walker and his family and such members of the crew as wished to accompany him: I had resolved never to sail with him again: I preferred to await the chance of rescue or to risk a voyage in one of the MINSTREL’S boats; and Jorgensen was like-minded.

“I think I can build a boat large enough for everyone,” said the carpenter, “if you can get the crew to help.” This they gladly agreed to do. I told off the strongest and most intelligent to assist Jorgensen; the others I detailed to gather and prepare food. Without loss of time work began. Merely making a start cheered the men remarkably; they were completely changed, so delighted were they at even a prospect of escaping from their island prison.

For the keel we used logs that had drifted ashore. Some of them, of Douglas fir, were undamaged and free from teredo borings, which indicated that they had not been long in the water. Dismantling the lighters and carrying the planks three-fourths of a mile through yielding sand was heavy work, as Jorgensen had discovered; but the crew, though relatively weak, pygmies alongside the brawny Dane, made light of it, required no driving; Jorgensen was an indefatigable worker, a competent and skillful carpenter, and no mean blacksmith. To me fell the sail-making, rigging, dismantling of lighters, general duty was not onerous, for the men were obedient and eager and often anticipated what I desired. Of greatest moment, there was no further illness: work was best, the only remedy for the ills of our brown crew. They toiled even harder when we began to fasten the planking in place and craft loomed in size.

In a few words I have narrated the progress of work, slow but satisfying; yet I do not wish to leave an impression that everything was easy. Lacking tools, for example, we had to manufacture them from shark hooks, which fortunately were of malleable steel. In this a portable forge and grindstone, which had been landed from the WANDERING MINSTREL before the wreck, were indispensable. Our try-pots, too, served as boilers for a stream box, in which we softened and made pliable the planks that went to to the bends of the boat; otherwise we should have had great difficulty. Spikes for our craft had to come from the lighters, and sails from the awnings I found in the MINSTREL’S wreck, while old hemp rope furnished oakum for the seams. More than once we proved that man can accomplish much–when he must. Even Hanker became interested, and I set him to picking oakum; but for some reason that I never could fathom, he and four men quit after ten days. Then I gave Hanker up as a bad job.

While the rest of us were building the schooner or were working at other appointed tasks, Walker was at his usual scheming, was spinning plans of where he would go and what he would do once he had arrived at some destination in the craft we were constructing. His life on Midway, however, was not always a sweet dream. One day Henry Walker, one of the captain’s sons, met me with word that his father wished to see me at once. “What is wrong?: I asked in alarm at the boy’s great agitation. “Is your father ill?” “No, Mr. Cameron,” the lad explained; “one of the Filipino boatswains stuck a spear into his cheek.” “I am sorry, Henry,” I said as gently as possible; “but you must tell your father that it is too late to do anything with the men. He should have let me shoot one of them the morning after the wreck. Why didn’t he himself shoot the man? Your father made his own bed, Henry, and there he must lie.” The wound was not serious, especially as it was a clean cut and soon would heal. I did not take the trouble to ascertain the cause of the quarrel.

We completed and launched the schooner, a strongly built vessel with good lines, of about fourteen tons. Moving her to the water from our building stocks, which were seventy yards from the beach, required four days, the use of rollers, much man power, and more sulphurous language. She was not christened with a bottle of champagne. A bottle had been at hand; now I regretted I had not saved it:–not a bottle of effervescent wine but one containing a few drops of whisky. I had picked it up on the beach and had dedicated it to other ends. After carefully moistening my lips with a little of the liquor, I had gone to the cottage and approached the skipper from the windward side. “Whisky, Mr. Cameron!” he exclaimed, all alert. “I didn’t know you had any!” “There’s precious little, Captain,” said I mournfully. “Not enough to share, much as I’d like to. I use it as medicine.” Time after time I repeated the farce until the bottle was bone-dry. But I had subjected the skipper to torment while the liquor lasted.

Now that the schooner was ready for use, Jorgensen and I announced our intention not to sail in her. Confounded by our decision, Walker tried to persuade us to go; he made lavish promises; even offered us part of the proceeds when the vessel was sold. Yet, I knew, if he did not, that whatever we received for her must go to our support, until we could shift for ourselves; no British or American officials in whatever country we reached would help us so long as we had the schooner or money realized by her sale. We maliciously made a counter proposal, that he give us the vessel on arrival; we were, however, not disappointed by his refusal. “The underwriters who insured the MINSTREL would not permit that,” he protested. “What rot!” said I. “Only the sails and rigging came from the MINSTREL’S salvage. But is it not strange, Captain, that the underwriters would permit you to sell the schooner and share the proceeds with us?” Day after day he tried in vain to move Jorgensen and me.

During this time the Dane and I did not neglect our duty; we put many barrels of fresh water aboard to serve as ballast and laid in provisions of eggs, smoked sea birds, fish salted and smoked, live turtles,–the whole stock sufficient for six weeks, during which the schooner should be able to reach the Marshall Islands. Now no excuse for remaining on Midway occurred to Walker; now he asked me the direct question: “Mr. Cameron, why won’t you sail with me?” “I decline to reply,” said I; “and you would be wise never to ask me again. Take Hander with you.” “Never!” he answered; “my life would not be safe with him and such scoundrelly men.” “You, Captain,” I reminded him, “are alone to blame. All our troubles are your fault. Then sail without a crew. You and your sons could handle the vessel; she is stanch; you would have good weather, now that it is summer; and the northeast trades would carry you the whole way to the Marshalls.” But Walker would not move without Messrs. Jorgensen and Cameron. Our labor had been wasted; there was no one to navigate the schooner. This turn reacted severely on the men: a Filipino boatswain and two of his countrymen died of scurvy–Those who kept their bodies clean, however, and followed my advice about exercise, were not affected.–All hands soon became greatly depressed.

At this juncture a storm cast the schooner upon the lagoon beach, but the only damage was the loss of some oakum from the seams, and she was refloated and anchored with what ground tackle we had. She was, however, ill-starred. Within a month or so one of the worst storms I ever saw, whether on sea or land, made an end of her.

Fascinated by a threatening aspect of the weather one evening in August, I scanned the sky. Its colors resembled those associated with typhoons: overhead, a dull and heavy gray; below and extending almost to the horizon from east through north to west, a sickly violet; beneath that lay copper to the dim line where sky and sea met. Little wind was blowing. When would the blast come? After waiting an hour I abandoned my watch and went to Redwood Cottage. “Have you,” I asked Jorgensen, “experienced any typhoons here?” He said he had not. “Unless I’m badly mistaken,” I continued, “we’re in for one. I hope this shanty will stand the gaff. Your work on it may be its salvation.”

At eleven o’clock that night the blow struck us. The building, it seemed, must go. The storm raised a terrific noise. Not a soul could sleep; every one was on edge to feel the house demolished at any moment. In their flimsy quarters the crew thought that the end of everything had come, and abandoning their huts, they huddled under the lee of our veranda. In their shacks they had been panic-stricken; now crowded together, close to omnipotent white men, lords of tempest, they were far braver. At daybreak the wind still blew fiercely, driving before it a hell of sand that penetrated into all parts of the house; sand in our hair, ears, eyes, nostrils; sand everywhere; we breathed it, swallowed it, gritted between our teeth.

Anxiety for the boat which Jorgensen and I generally used led me to suggest that we venture into the storm and ascertain whether it was all right. Out we sallied on the lee side of the house; as we rounded the corner the wind flung us back. To see was impossible; though the time was forenoon, a dun night enveloped the world, while rain and furious sand stung our faces like needles. We lashed on our clothing to prevent it being literally blown from our bodies; then we made another essay; yet still we could not stand against the storm, even by crouching almost to the ground, and at length we crawled. Finally we attained the place where we had left the boat. It had vanished. What now? Sitting with our backs to the gale, shouting mouth to ear in order to make ourselves heard above the awful elemental roar, we discussed our course. We decided to search for the boat to leeward, but not to venture too far, lest we lose all sense of directions and so fail to regain the house. Within fifty yards we stumbled upon the craft, half buried in sand, with some of the planking broken; whether it had been damaged otherwise we could not ascertain.

Then we retraced our steps;–we crawled, rather, on the flats of our bellies, guessing our way; moving at the pace of a snail; holding our eyes shut fast against the flying sand. Our progress was small, and even that little might be in a wrong direction. Never have I had another such experience. We clutched each other’s hands, I slightly in the lead to shield Jorgensen, who was beginning to despair. “I can go no farther, Cameron,” he moaned. “You damned fool!” roared I,–“Roared,” did I say?” I must have squeaked like a bat in that hell,–“You damned fool! What! Give up and die? Sand will bury you. We’re near the house. Spurt, and we’ll make it!” “I’m done for, Cameron,” he gasped. “Leave me here. You go on.” See you damned first,” said I;–and without me damned he would have been. Then I clouted him hard in the face. A stiff blow to the jaw is an excellent spur, believe me. “Now will you try?” I demanded. He made an effort’–funked; rallied and again failed; but with striking and cursing him and resting frequently, I got him to the hut. Each of us was soaking wet, grievously hungry; our faces were bloody from the scouring of the sand. Between three and four o’clock in the afternoon, when it had blown for sixteen hours, the storm suddenly died. What a sight we saw! Changed, remolded, was the whole island; the brush, scanty at best, was stripped of leaves and seemed scorched as by fire; all the grass was withered; here was a new mound, there an unexpected pit. Fortunately for us the birds had not been blown away, though I cannot understand why they were not. The boats, shanties and house all had been damaged to such an extent that repairs required a week. Far worse was the fate of the schooner: again she had been cast high upon the sand and was now beyond restoration; masts and rudder were gone and the port side was smashed. The typhoon had made sure that neither Walker nor Cameron would ever navigate that craft.